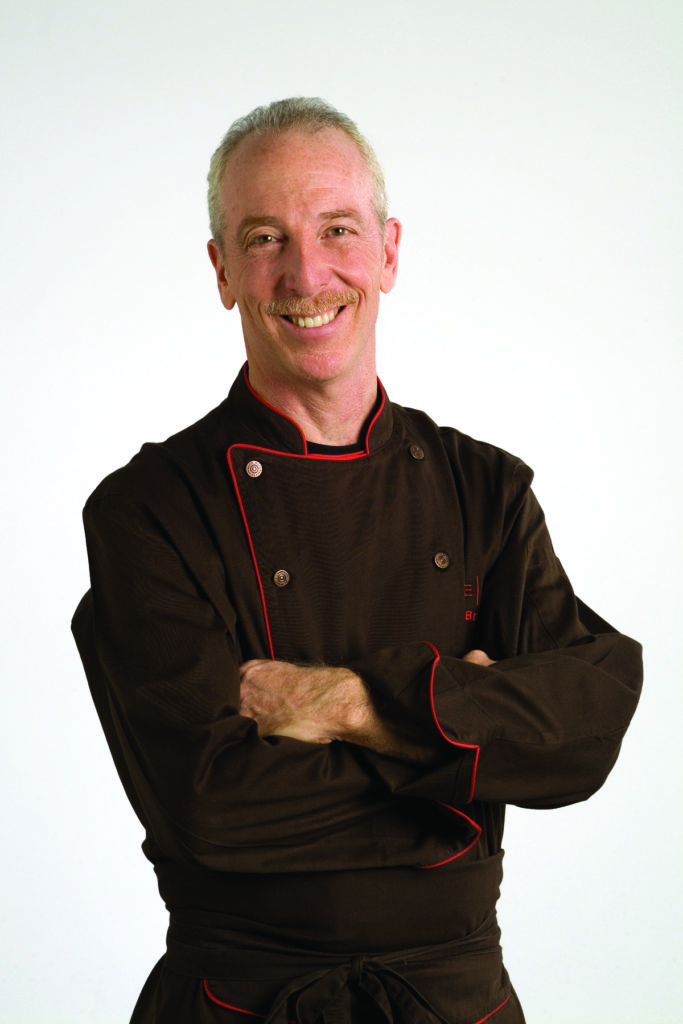

Zack Bruell makes dining dramatic

Artfully designed main course at Cowell & Hubbard. PHOTO | David Hagen, Kalman & Pabst

By Carlo Wolff

PHOTO | Epstein Design Partners

Zack Bruell talks like he was an ornery young man. Not only did he defy his father in his career choice, he turned his back on the military and used his gifts to create successful restaurants, beating the odds in that business.

A compact man with a wry sense of humor, Zachary Ernest Bruell made his initial mark in Cleveland’s suburbs nearly 30 years ago when he opened Z Contemporary Cuisine, a minimalist restaurant with two incarnations: Tower East in Shaker Heights and Eton Chagrin Boulevard in Woodmere.

Bruell is totally urban now, his restaurants all in Cleveland: Parallax, in the Tremont neighborhood; Table 45, in the InterContinental Hotel Cleveland on the Cleveland Clinic campus; L’Albatros Brasserie + Bar, in University Circle; and Ristorante Chinato and Cowell & Hubbard downtown. In late July, he opened Dynomite, a walk-up burger joint, in the glass pavilion on Star Plaza across from Cowell & Hubbard.

All of his establishments feature open kitchens. As Bruell says, “You’re right there, front and center.” Bruell notes the failure rate of restaurants is 90 percent within six months of opening.

Bruell considers himself a pioneer in Cleveland’s acclaimed fine dining scene, also known for such players as Michael Symon, Jonathon Sawyer – and Doug Katz, who apprenticed with Bruell at the first Z when Katz was 14.

Bruell also views himself as part of a team, a conductor rather than a player. That was not always so.

The Shaker Heights native, who with his three sisters grew up in a home with live-in help, took his own sweet time to settle down. Until the 2000s, rebellion might well have been his middle name.

A former scratch golfer (“I’m a shadow of my former self”) who’d rather be on the course than anywhere else, Bruell was somewhat of a hippie. When he was a freshman at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, he quit the golf team because he wouldn’t cut his hair, as his coach demanded.

Bruell also got the itch to cook that year. “The way I started cooking is when I went to Penn, first semester the food was so bad – Monday it’s this, Tuesday it’s that, Wednesday it’s this – then you start the rotation over again. The second semester, I told my dad, just give me the money for the food program and I’ll fend for myself.”

Bruell had a hot plate. A kid down the hall had a toaster. They made a meal every day. Bruell gained 10 pounds that semester.

Bruell was drafted after his freshman year and entered the Coast Guard reserves. It was 1972, in the thick of the Vietnam War.

“They were just taking everybody,” including a “nice upper middle class Jewish kid who went from the Wharton School of Finance to a boot camp in Cape May, N.J. I was in with a lot of people who had been in jail,” he says, laughing. “There was more freedom in jail than there was in this boot camp.”

He celebrated his 20th birthday there.

To mark the day, Bruell’s drill sergeant marched him into the barracks, told him to hoist his 80-pound duffel bag over his shoulders and run around the quadrangle until told to stop. “He had the rest of the company sing Happy Birthday,” Bruell says with a sideways smile.

The interiors of Ristorante Chinato. PHOTO | Kevin G. Reeves

Civilian Zack

Bruell left the Coast Guard Reserve with a general discharge, one rung above dishonorable. When he came home, he told his father, a manufacturer’s representative in the builders’ hardware industry, that he wanted to become a chef.

“This was 1972, ’73,” Bruell recalls. “He looked at me and says, are you out of your f—— mind? He says you can make more money as a garbage collector, and at the time, he was right. … I wanted to become a chef so I could open a restaurant. I’m very independent, to a fault.”

His father was more than chagrined when Bruell opted for a food career instead of taking over the family business. But over time, Ernest and Marjorie Bruell came to support their son’s achievements. Ernest died in 1984 as Bruell was negotiating for his first Z; his dad never saw any of his places. His mother, whom he took care of during her last two years, made it to all of them. Marjorie died in June 2012.

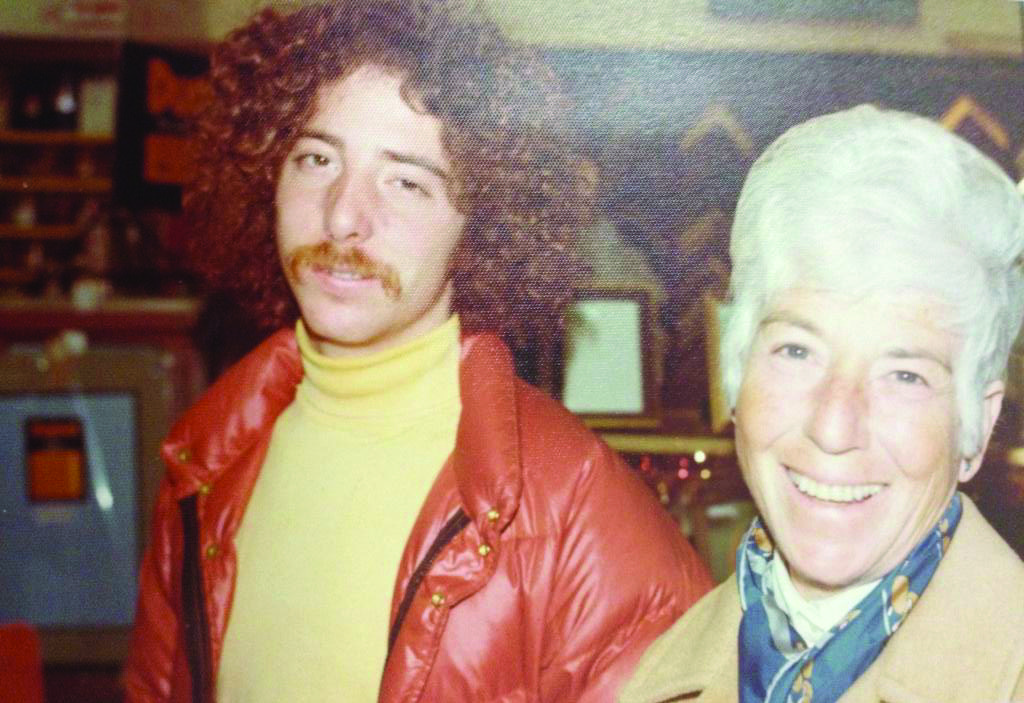

Zack Bruell and his mother Marjorie at the University of Colorado Boulder in 1974. PHOTO | Zack Bruell

Following the Coast Guard experience, Bruell transferred to the University of Colorado Boulder, earning a degree in business from there in 1976. “I hated what I was studying, but I knew it was important to have a college education, and I knew I needed that business knowledge,” he says. Although he first aimed his sights at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, N.Y., he instead chose The Restaurant School, a Philadelphia-area institution “for idiots like myself who wanted to open up small fine-dining restaurants.”

Bruell developed his sense of style in Philadelphia. Mentored by gay chefs catering to wealthy diners and entertainment folk, Bruell began to prepare and cook fusion food well before the term gained currency. He also developed a taste for Philly Soul music.

How the food looks should sync with the restaurant ambience, Bruell suggests. “It’s dining as theater,” he says in a recent interview at Cowell & Hubbard, his restaurant at the heart of Cleveland’s theater district. “This is theater. And this was before that existed. Dining rooms back then were all very formal. There was no in-between. This was the in-between.”

As a chef taking his cues from Lewis Bolno, who opened 20th Street Café, an all-white (the décor, not the clientele) restaurant off Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square that catered to the well-heeled, Bruell began to conceive a restaurant of his own.

“The whole idea of that restaurant was the same idea I had at Z: that the color would be provided by the patrons,” he says. “In Cleveland, people don’t understand that. Back then, there was no music in these restaurants. This guy, he was a window designer. That’s what this restaurant was. Imagine Soho or the Village in the mid-’70s. Things were changing.”

The West Coast beckons

In 1980, faced with a variety of choices, Bruell moved to Santa Monica, Calif., joining Michael McCarty, whom he’d become friends with at the University of Colorado Boulder, at Michael’s, then considered one of the nation’s top restaurants. At 28, Bruell was the restaurant’s oldest staffer. Money was not an issue at McCarty’s legendary restaurant, where the average lunch check was $60, a lot of money – particularly then.

“When price is no object and the customer’s going to pay, you can work with whatever you want,” Bruell says. “In 1980, I was working with white truffles, black truffles, beluga caviar, you name it. If it was in season in the world, we were working with it.” The advent of airfreight meant chefs no longer had to depend on rail. “You could ship something from Europe in two days,” Bruell says. “This is the exact opposite of what’s going on now.

“Raspberries used to be seasonal. Now you can get raspberries year-round, because now when they’re out of season up here you can just go to the southern hemisphere. We were doing that kind of stuff before it was common. Our market was the world. There’s a huge expense to that.”

While he’s not Mr. Local when it comes to ingredients, Bruell tries to use locally grown products at his restaurants and works closely with Cleveland Crops, which he called the city’s largest urban farming group. He’s puzzled by the cost of local produce.

Coming home

Bruell opened Z Contemporary Cuisine in 1985 in Tower East in Shaker Heights. Designed by Bill Blunden, a Cleveland architect who also designed the second Z iteration and Table 45, it was minimalist, even austere.

Zack Bruell has this coffee custom roasted for each of his restaurants. He also markets it under the name Z through Heinen’s Fine Foods. PHOTO | Epstein Design Partners

(Blunden, the architectural consultant to Cleveland Clinic, says a restaurant is “a combination of theater and gallery, as well as dining,” in the book, “Successful Restaurant Design.” Blunden told authors Regina Baraban and Joseph Durocher a restaurant designer wants to create a space “that has energy but still allows for intimacy. It should provide choices for people, from the single diner to the couple, from groups of friends to groups of business associates.” Bruell’s restaurants fill those bills.)

Ron Reed of Westlake Reed Leskosky designed Bruell’s other restaurants.

Bruell ran Z at Tower East until 1992, when he moved it to Eton Chagrin Boulevard next to Kilgore Trout, one of his favorite clothing stores. He was working 90 hours a week, six days a week. He did that for 10 years straight. He burned out.

In 1995, his 7-year-old daughter Frederique wanted him to come to a father-daughter dance for the Girl Scouts. He arranged for another chef to cover for him. That other chef was a no-show.

“That was it,” he says. “That was the turning point.

“What am I doing here?” Bruell thought to himself. “What am I going to prove? I want to see my kids grow up. I want to be part of their lives.”

He sold Z, took a year off and played golf.

In the fall of 1996 Ken Stewart, a well-known Akron restaurateur, hired him as a consulting chef for three months. The gig lasted eight years. His business buffeted by 9/11 and the recession, Stewart cut Bruell to half time and half pay. That was turning point No. 2, time for Bruell to create another restaurant.

The Bruell array

In 2004, Bruell and David Schneider, whom Bruell had mentored at Z 2.0, opened Parallax. Although he thought it would do modest business, catering to “local hipsters,” his old clientele shortly discovered it – and it took off.

Two days into Parallax, Bruell’s employees upended him, creating turning point No. 3. “I’m 52 years old, and I’m cooking on a line, which is very uncommon for somebody that age,” says Bruell. “It’s a young man’s game. It’s physical. So the chef and the sous chef looked at me and I knew what they were thinking. They say, why don’t you go over to the other side of the line over there? We got it covered.”

Bruell now employs about 250 people.

“I stepped off the line and became an expediter. Instead of becoming a player in an orchestra, I became a conductor, and I never knew how to do that. They changed my life. I can’t let them fail, because it’s my business … it can’t fail. You’re only as good as your last meal. Now I was able to watch every dish that came out – and finish it.”

What drives him? Impulse and boredom.

“They are a canvas,” he says of his eateries. “You know how you feel when you say I’m in the mood for this type of food? ‘I’m in the mood for sushi. I guess I’ll open a restaurant for sushi. I’m in the mood for Italian food. I guess I’ll open an Italian restaurant.’ It’s like looking in your own refrigerator. It’s filled and there’s nothing to eat.

“We open these places out of boredom,” says Bruell, who no matter how disparaging he sounds, is proud he created businesses that got his three kids through college. “I get bored. This is very repetitive.”

A master of blend who learned about Thai food in Philadelphia and about cooking light in California, Bruell nevertheless downplays his art and craft.

“I’m not finding a cure for cancer,” he says. “I’m providing an escape for people. I don’t consider what we do is really important in the scheme of changing life. I’m not a doctor. I’m not saving lives. To think that you’re important because you do this, I look at that as that’s a joke.”

More and more people would beg to differ. js