Book suggests new ways to think about Cleveland

By Carlo Wolff

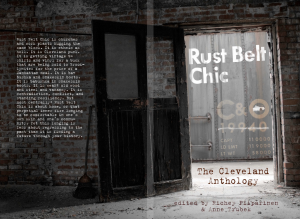

Anne Trubek chooses her words carefully when she discusses the concept of “Rust Belt Chic,” the name of the “Cleveland Anthology” she and Richey Piiparinen published last fall. She doesn’t speak gingerly of the book itself, however; she’s proud of the collection of writing the two assembled and published in a mere two months last year.

The careful part enters into use of “rust belt chic” as a description. The term is catchy, indeed, particularly for Greater Cleveland residents familiar with the region’s trials, its gumption and – Trubek suggest – increasing optimism about its future.

“Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology” spans essays, photography and poetry all geared toward a critical celebration of Cleveland. For Trubek, the book is a form of giving back to an area that matters to her. It’s also a way to get people thinking about the city: what’s deplorable, what’s to tout, what’s high style – even what to do to improve the place. One way to get at the thought behind the book is to separate its elements into “rust belt” and “chic.”

The book is “an exercise that gives voice to a culture with a history of voicelessness,” Piiparinen says. That Greater Cleveland is associated with decay “has been the mesofact of our region,” a “fact that drives reality but not the total reality. We wanted to create a book that expanded beyond … all that’s lost.”

One of the book’s aims is to change the psychology of the region by helping it identify and affirm itself, suggests Piiparinen. There’s been a “huge diaspora of rust belt culture all over the country, so there’s a lot of potential to bringing all the human capital, intellectual capital and financial capital back,” he says.

Another approach is to consider “rust belt” a view of the past, chic” as looking forward. An image of a renovated home that keeps a brick chimney exposed, rather than painted, may appear in the mind’s eye.

“The goals of the book are to showcase local writers and develop this idea of rust belt chic, which focuses on what is distinctive about Cleveland and preserving that as we grow … as the region develops economically, there is sort of an economic development angle to it,” Trubek says in an interview at Dewey’s Coffee on Shaker Square. “It’s a very exciting time in town, and I think that what people are doing, a lot of it is looking to the past, from the very obvious things of renovating old warehouses and preserving some of the original industrial interiors to … a real emphasis on buying locally and frequenting local merchants.”

Giving back

“Rust belt,” of course, also refers to the industrial past of the Midwest. “Chic” is more generic. What ties them together is continuity and the notion of sustenance. It’s closely related to Trubek’s own motivation in conceiving the book: giving back, or what Trubek identifies as “mitzvah.”

An associate professor of English at Oberlin College who moved to the area from Philadelphia in 1997, Trubek writes for local and national publications, including a “fair amount of pieces that are Cleveland-related,” she says. In “Rust Belt Chic,” she wrote about Cleveland poet Hart Crane; she also wrote about Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster for Smithsonian.com, the Smithsonian Institution’s online magazine.

About a year ago, Trubek began organizing workshops for freelance writers seeking national outlets and came across Piiparinen’s work. An urban policy consultant, he has been featured on NPR’s Morning Edition and in the online magazine Salon. After discovering common concerns and ambitions, they decided to create “Rust Belt Chic” as testimonial to where they live. Trubek said it ”let us put our stamp on what’s happening in town rather than having it described by outsiders who are kind of observing what is happening in Cleveland.”

Trubek left Oberlin for Shaker Heights in 2006 partially because of the area’s Jewish community. She sees a lot of ”boomeranging” in that social segment. ”You grow up here, you go away for college, you establish your professional life, but then you return to raise a family,” says Trubek, a Reform Jew who attends The Temple-Tifereth Israel. Her 13-year-old son Simon attends the Ratner School in Pepper Pike.

RBC: a complex kid

Piiparinen’s essay, “Anorexic Vampires, Cleveland Veins: The Story of Rust Belt Chic” sources the term to Joyce Brabner of Cleveland Heights. In 1992, Brabner, the widow of the late cartoonist-social commentator Harvey Pekar, said to an interviewer, “I’ll tell you the relationship between New York and Cleveland. We are the people that all those anorexic vampires with their little black miniskirts and their black leather jackets come to with their video cameras to document Rust Belt Chic.“

“We’re just basically these little pulsating jugular veins waiting for you guys to leech off some of our nice, homey, backwards Cleveland stuff,“ Brabner continued.

Trubek says, “I think it’s important to get the complexity of the term. On one level, and this is what Joyce Brabner is referring to, it refers to a snotty perspective of those from the coasts who think that the blue-collar aesthetic is cool but they are exploiting it, but on the other hand the term is saying there are specifics of this area, this city (Cleveland) in particular, that are distinctive and unique and we should celebrate them and build upon them rather than be ashamed or shy away or try to be glitzy in a different way. The polka hours hipsters are into now are a great example of taking an aspect of Cleveland’s past and culture and celebrating it in a new way by a new population.”

RBC fashion

Those ’90s women in miniskirts and black leather jackets Brabner disdained may have symbolized New York fashion, but rust belt chic style is harder to sum up, Trubek suggests. Citing a Bert Stratton drawing of a guy in a Browns T-shirt “with his stomach showing and a can of cheap beer,” Trubek says parody is one way to view it.

Another honors and freshens the city’s past. “Buying clothes made in town or sold by local boutiques would be not just a tongue-in-cheek aspect of it but a more serious aspect,” Trubek says, citing names linked to Cleveland’s legendary garment industry: The Printz-Biedermann Co., Richman Brothers, Joseph & Feiss Co. and Ohio Knitting Mills. At one point, 200 Jewish families were in that business, which at its peak employed 7 percent of the Cleveland work force, she says.

Ohio Knitting Mills, revitalized by Cleveland Heights man Steven Tatar, is the survivor. Tatar, says Trubek, is doing “exactly what we’re talking about: renewal of the past, attention and respect for it, and making it work for today.”