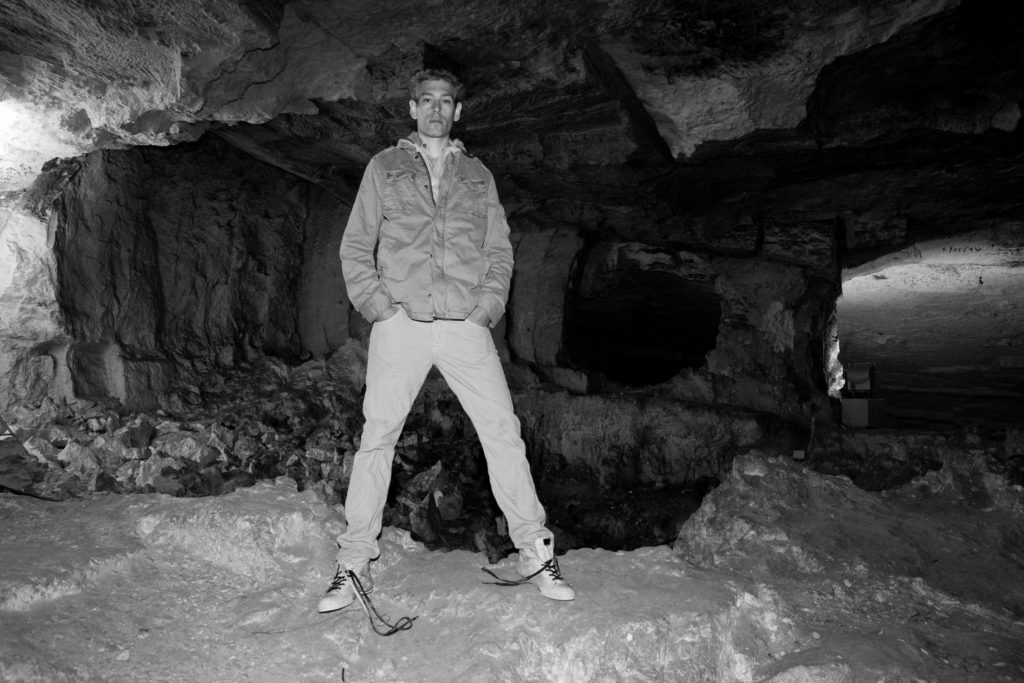

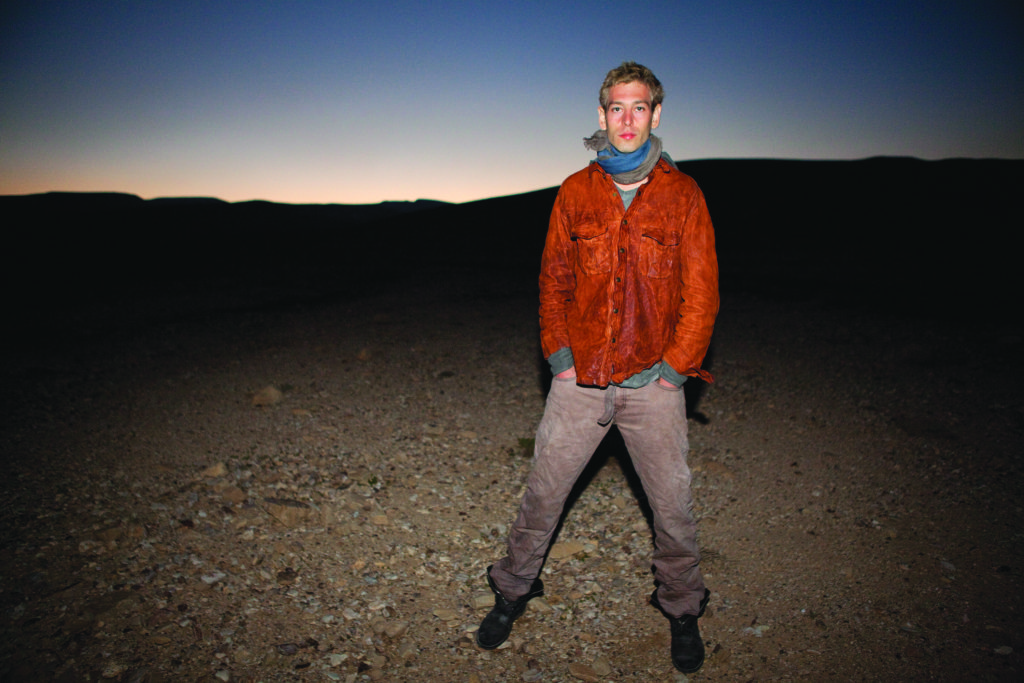

For Jewish rock star Matisyahu, God is always in style

PHOTO | Mark Squires

By Carlo Wolff

PHOTO | Mark Squires

Matisyahu is on a roll. Not only is he on tour, he’s recording a new album at Studio G Brooklyn (the “G” stands for the Brooklyn neighborhood of Greenpoint) and talking about “Spark Seeker,” the first album he has released since he and his family relocated to Los Angeles from Brooklyn’s Crown Heights section two years ago.

Matisyahu is a thoughtful man who takes pains to make himself clear. Which isn’t that easy when you’re an artist who has made a career of upending expectations and mashing up styles.

Matisyahu and his band, Rebelution, came to Cleveland for “Fall Kickoff 2013: #TTB (Thinkin’ Throwback),” a BBYO program on Sept. 1 at the Mandel Jewish Community Center in Beachwood. Matisyahu launched a six-week tour Aug. 7. He does not perform on Shabbat.

Formerly known for performing in Chasidic clothing – including a black kipah with tzitzit ritual fringes rocking beneath his white shirt – Matisyahu has changed. He is clean-shaven now, his clothing casual. He no longer feels the need to adhere to Orthodox ritual, he suggested.

On Dec. 13, 2011, Matisyahu, who made himself into a unique poster boy as a bearded, Chasidic Jew when he released his debut, “Live at Stubb’s,” in 2005, posted a beardless picture of himself on Twitter, adding these comments on his website:

“No more (Chasidic) reggae superstar. Sorry folks, all you get is me … no alias. When I started becoming religious 10 years ago it was a very natural and organic process. It was my choice. My journey to discover my roots and explore Jewish spirituality – not through books but through real life. At a certain point I felt the need to submit to a higher level of religiosity … to move away from my intuition and to accept an ultimate truth. I felt that in order to become a good person I needed rules – lots of them – or else I would somehow fall apart. I am reclaiming myself. Trusting my goodness and my divine mission.”

PHOTO | Mark Squires

The image and such comments gave him a new profile and restored him to pop consciousness. Now Matisyahu, known for blending Jewish themes with reggae rhythms and beatbox accents, is firing on all cylinders, musical and otherwise. He also recently launched a YouTube campaign, “Love Like a Warrior – Stands for Change,” a nonprofit group designed to promote a non-judgmental, inclusive society. The campaign, which ran in May, served as a preview for “Spark Seeker,” which was released in July. It invited musicians to craft their own versions of “Live Like a Warrior,” his newest single, to spread messages deploring bullying and encouraging self-empowerment.

Matisyahu, who was born Matthew Paul Miller in West Chester, Pa., 34 years ago, recently devoted 15 minutes of his crammed schedule to speak with Jstyle. Actually, the phone interview took 18 to 19 minutes, the limit his publicist allowed (he had another phoner scheduled immediately afterward), but he could’ve gone on longer.

He essentially addressed one question: Why did he “feel the need to submit to a higher level of religiosity?” The conversational thread follows.

One reason he joined the Lubavich movement and became a Chasidic Jew was to forge a deeper bond with God, he says. But the motivation was more complex.

“My initial attraction with Judaism, which wasn’t necessarily based about the religion, was more in a kind of desire for connection with God and with Jewish spirituality and a search for my identity,” he says.

PHOTO | Mark Squires

When he began to shift from his Reconstructionist upbringing to the Orthodox framework, he says, he was already on the way “to spirituality or a path towards God and I had had some rich experiences with Judaism” and started “to explore more in depth the spiritual side of Judaism which came in and out of connecting with the religious side.” His search included visiting various synagogues; consider it a spiritual form of window-shopping.

“I wanted to learn how to pray better,” he says. “I was looking for that immediate, spiritual, emotional connection with God.”

His quest also led him to want to look the part, so he began wearing a yarmulke and tzitzit to see what that would feel like. He was trying to unite the inner and outer man, the prayer with the image. The journey was lonely – until he connected with a chabad rabbi, entered into the Orthodox community of Crown Heights, and religion and the rules began to synchronize. His quest also entailed a form of discipline.

He had “lived a little bit of a wild kind of life,” Matisyahu says, and felt guilty about things. Religion kicked in as he attempted to forge a life that did not involve “sex, drugs, that kind of stuff,” and he came to embrace Orthodox Judaism. “There was no going halfway,” he says; he couldn’t live by some rules but not others.

What was the most difficult part of shedding his Hasidism?

It’s not a matter of parts, he says, but of incremental, below-the-surface changes. “Over the span of 10 years, from the time I became religious to that day, there was a lot of movement for me,” not all of it visible. “Even though I had sort of started to interpret Judaism in my own way and begun to loosen up on some of the rules and focus on a lot of different aspects,” there was a “shift where I really let go of the idea … I stopped trying to work within the guidelines of Orthodox Judaism.

“I shifted from seeing the religion and the rules as actual rules to it being more of a guideline. It’s like when you’re talking to God straight up there are no rules. The guidelines are supposed to bring you to that.”

PHOTO | Mark Squires

Shedding Orthodox strictures and trappings was liberating, he suggested. His shaving was an expression “that this is no longer about transgression or sins, that the laws are not about God expecting us to do something. It’s no longer that God wants us to be a certain way or to do certain things … and the goal is to talk to God. And I do. And once I felt like I had that, I felt like I didn’t necessarily need to keep fitting myself into the rules.

“So this touring musician is who I am and I’m a creative person, but I was always trying to blend it in. Now I take from what I’ve learned – the Hebrew, the concepts, the ideas, the emotions, the feelings – and incorporate that, and that feeds my soul and who I am and the music that I make.”

What he has learned is “to not judge. I’ve learned that as a person through this experience. No one has the answers.”

As for fashion, “I still, like, love the idea and look of a Hasidic guy, not styled, like, in a designer way. When I first became Chasidic, it was all about the idea of why I did it, it was all about getting away from style. But then that became my whole entity; I was wrapped up in that.”

By letting go in December 2011, “it was sort of the same experience, just happening in an opposite way.” js