History through HER story

By Ed Carroll

Thinking about the Holocaust, you get lost in the horrors and atrocities – incredible pain, millions of lives lost and trauma that has lingered throughout generations.

During this suffering, Jewish people also tried to go about their daily lives, or what was left of them. While there are countless accounts of what Jewish life was like during the Holocaust and World War II for adults, there aren’t as many records of what it was like for children. But, a new exhibit coming to the Maltz Museum in Beachwood, starting Oct. 25, will share the perspective of a particular 14-year-old girl: Rywka Lipszyc.

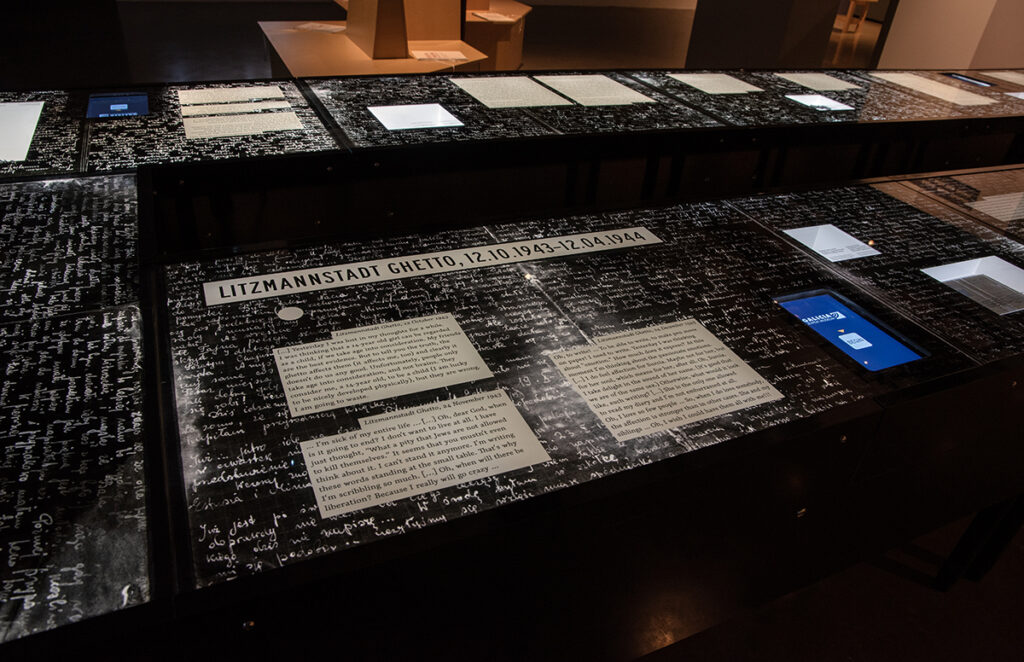

The exhibit, “The Girl in the Diary: Searching for Rywka from the Lodz Ghetto,” is a traveling exhibition from the Galicia Jewish Museum in Kraków, Poland. It documents her life and shares Rywka’s diary in 112 pages, which she wrote while living in the Lodz Ghetto between October 1943 and April 1944. The ghetto in Lodz, Poland was the second largest and ended up lasting longer than most of the other ghettos because it served like a large production factory for the Nazis.

The exhibit itself includes 30 objects, featuring the diary translated into English and interactive displays of other diaries that survived the Holocaust. The exhibition also includes supplementary commentary from historians, doctors, rabbis and other experts to provide context and insight.

Historical context

Rywka was born in 1929 in Lodz, the eldest of four children. By the time she started her diary, her father, mother, her brother and a sister were already dead, all either directly by Nazi hands or due to starvation. She and her surviving sister were put in the custody of her aunt, who subsequently died. Their aunt’s eldest daughter – Rywka’s cousin – took care of the girls, with her other two cousins also helping out.

Right away, there are a few unique things about Rywka’s diary compared to other diaries found from the Holocaust. Tomasz Strug, deputy director and chief curator at the Galicia Jewish Museum, who helped curate the exhibit, says Rywka had a handful of extra privileges not afforded to most members of the ghetto.

“She got some sort of additional arrangements, such as additional days off from work, a separate soup kitchen or a small space where you could plant tomatoes,” Strug says. “It’s unclear who got this privilege and who didn’t, but it generally means you or your family was connected with the Jewish administration of the ghetto. It wasn’t very common, and it may be one of the reasons she survived the ghetto.”

One big difference between Rywka’s story and a more famous diary like Anne Frank’s was unlike Frank, who was more of a secular Jew, Rywka was from an Orthodox family and spent a lot of her diary lamenting she was unable to practice her faith the way she wanted, such as having to work on Shabbat. Strug also says that despite Rwyka’s Orthodox upbringing, she wrote her diary in Polish, which suggests she had some education.

“(Rywka’s diary) presents an extremely rare point of view,” Strug says. “Most of the diaries we are able to recover are written by either secular or assimilated Jews, and if we do find one from an Orthodox perspective, it’s written by men or boys. … But in her diary, it’s the most important point of departure for her (compared to other diaries found) – her religious beliefs. We find God on every page of this diary.”

And, it’s unique that her diary chronicles a later period in the Holocaust, one not often seen documented as it was closer to the end of the war, he says.

Another point that stands out: there aren’t really any men in her diary, at least not as important characters in her story.

“Rywka’s world is mostly of women,” Strug says. “When she starts writing in the diary, her father and brother … are both dead. There are no male characters in the diary. If they appear, it’s in the context of something else. … She’s writing about her sisters, her cousins, her girlfriends from school.

“She’s writing like every other girl (today): ‘I don’t like this girl because I think that my poem was better than her poem, and I wouldn’t really give her an ‘A’ for this poem, so I don’t know why the teacher gave her an ‘A.’”

Bringing her story to the Maltz

For Maltz Museum Managing Director David Schafer and the museum’s exhibition committee, bringing “The Girl in the Diary: Searching for Rywka from the Lodz Ghetto” to the museum was an easy call.

“The diary is a primary source document telling a present-tense perspective, which gives us as an audience the purest form of understanding of her experiences,” Schafer says. “We are privy to how this 14-year-old girl, whose formal education ended at age 11 when the Nazis invaded Poland, lived through daily life in the Lodz Ghetto. As a young girl, writing her unguarded accounts with sophistication beyond her years, her powerful insights shed light on a dark time with hope and faith. As a note of interest, the final page of the diary is unfinished, which is one of the most compelling things about this story. Who was she? What happened to her? Her story is left unfinished.”

He also says the museum is proud to give voices to more stories of girls and women of courage, like Rywka.

“History is often told through the perspective of men and through the voice of men,” Schafer says. “Rywka’s diary, however, gives us a young woman’s perspective and insight, but it doesn’t end there. In the book and therefore also the exhibition, women interpret her diary – female psychologists, historians, doctors and rabbis. … We hope audiences look to this history as a way to better understand our present and consider a better future.”

The traveling exhibit “The Girl in the Diary: Searching for Rywka from the Lodz Ghetto” will be on view from Oct. 25, 2023 through April 28, 2024, at the Maltz Museum at 2929 Richmond Road in Beachwood. An exhibit launch event will be held at 7 p.m. Oct. 25, featuring Tomasz Strug, deputy director and chief curator at the Galicia Jewish Museum. In celebration of the launch, museum general admission is $5 from Oct. 25-30. Learn more at maltzmuseum.org/GITD.